Neural mechanisms of memory and interactions with reward learning systems

At Johns Hopkins University and the University of California, Berkeley, I worked in the lab of Professor David Foster (currently Professor at the University of California, Berkeley) studying how patterns of neural reactivation in the hippocampus brain region of rodents, called hippocampal replay sequences, react to changes in reward in spatial environments. These replay sequences occur while the animal is stationary or even asleep, but replicate the ordered pattern of activity that would be observed if the animal actually ran a specific trajectory through a given environment, and are therefore thought to depict remembered or imagined experiences for the purposes of planning, learning, and memory consolidation. Combining reversible inactivation of dopamine neurons, high density electrophysiological recordings, and data analysis methods including Bayesian decoding and mixed effect linear models, I showed that the normal tendency of replay to preferentially occur at locations with high reward value depends critically on reward-related dopamine signals (article link). I also demonstrated that the rate of replay occurrence was correlated with reward prediction errors, indicating memory-related neural reactivations are targeted to environmental locations where more value learning should be completed.

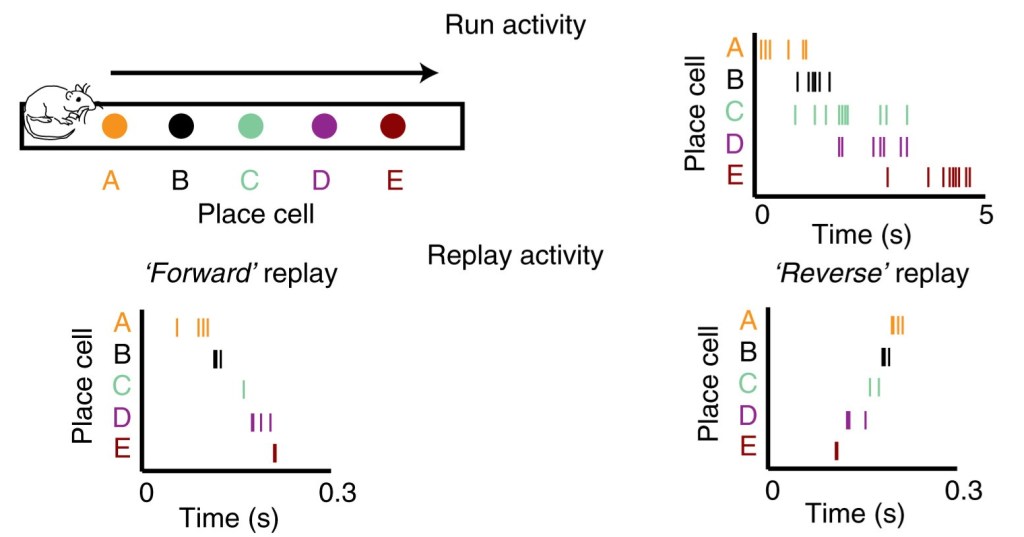

The sequences of neuronal activations observed during active exploration of an environment are recapitulated during stationary or rest periods in temporally compressed, and sometimes reversed, order. Tick marks indicate action potentials fired by a given neuron. Adapted from Ólafsdóttir HF, Bush D, Barry C. The Role of Hippocampal Replay in Memory and Planning. Curr Biol. 2018 Jan 8;28(1):R37-R50. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.073.

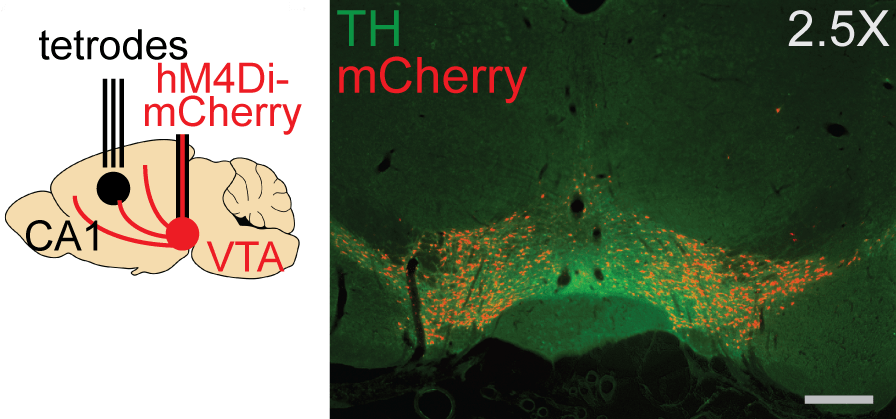

By combining high density tetrode recordings in hippocampal area CA1 and reversible inactivation of dopamine neurons, I showed normal reward-related dopamine signaling is necessary for replay sequences to be targeted to newly discovered, highly rewarding locations. Tetrodes recorded from the CA1 region of hippocampus (left panel), while dopamine neurons in the VTA, visualized here in green by staining for the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), expressed the inhibitory DREADD hM4Di, visualized here in red by co-expression of mCherry (right panel). Adapted from Kleinman MR, Foster DJ. Spatial localization of hippocampal replay requires dopamine signaling. Elife. 2025 Mar 24;13:RP99678. doi: 10.7554/eLife.99678.

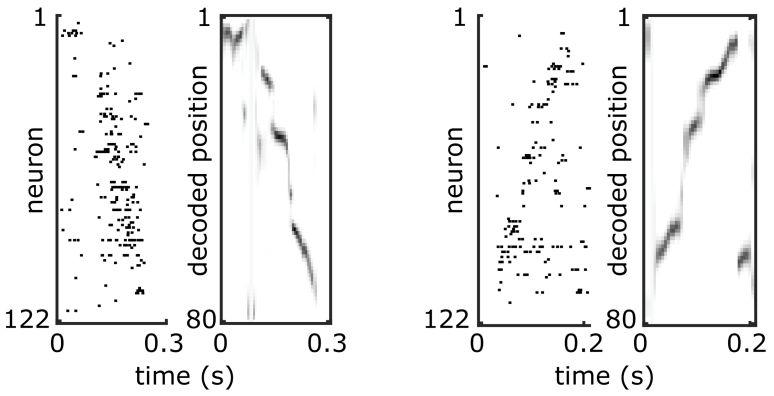

In a separate project, I tested assumptions about replay sequences, which have previously been described as being composed of stationary representations at discrete attractor points that are punctuated by discontinuous jumps between attractors. By reanalyzing data collected previously in the lab, I instead showed that the apparently stationary spatial representations were actually drifting coherently in the same direction that subsequent jumps would occur, revealing a lack of obvious auto-associative dynamics. I further used dimensionality reduction and similarity and clustering analyses to show that during replay sequences, the rate of movement through the high-dimensional neural state space was correlated with the velocity of movement through the represented spatial locations, providing evidence in favor of certain models of replay sequence generation.

Example replay sequences showing “jump” and “drift” dynamics. Neurons are ordered according to their preferred firing location on the track. Tick marks indicate action potentials fired by a given neuron. The spatial position represented by the ensemble of neurons in each time bin is determined using Bayesian decoding.

I also collaborated with John Widloski (currently Scientist II at the Allen Institute) and David Theurel (currently Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of California, Berkeley) on a project examining how the firing rate variability of neurons in the hippocampus changed between active locomotion through an environment and “imagined” movement through the same environment, in the form of replay sequences. Using innovative statistical tests and modeling, we demonstrated a highly consistent spatial code and neuronal firing rate variability across these two states, despite replay sequences being temporally compressed by a factor of 10-20 times and occurring in the absence of external and internal sensory cues related to movement.

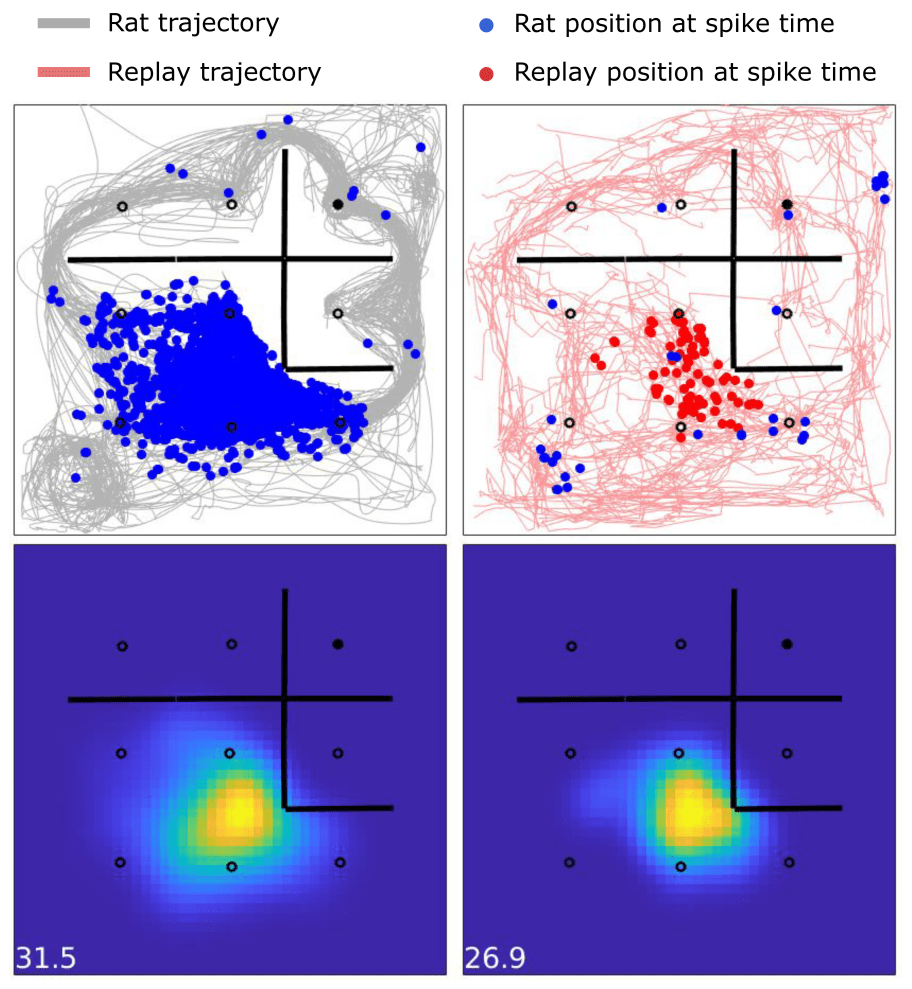

The selectivity of hippocampal place cells is preserved across actual and simulated experience. The activity of one individual hippocampal place cell in a 1 meter by 1 meter arena is shown across two different behavioral states, when the animal is actively exploring the environment (left) and when the animal is stationary but hippocampal replay sequences are exploring the environment (right). The heatmaps on the bottom show firing rates across position, with the peak rate indicated (bottom left). The preferred location, peak firing rates, and variability in firing rates across repeated passes through the environment are similar, suggesting the same mechanisms and statistics are driving learning in online and offline states.

Prefrontal cortex contributions to visuomotor decision making

At Yale University, I wrote my PhD thesis, “Temporal Processing and Multitasking in Prefrontal Cortex,” on work I completed in the lab of Professor Daeyeol Lee (currently Professor at Johns Hopkins University) investigating how prefrontal cortex neurons were able to simultaneously multiplex signals related to multiple sensory, motor, and internal variables. I designed a novel behavioral task requiring non-human primates to attend to and estimate the duration of two visual targets, finding that (1) animals were able to flexibly time two temporal intervals simultaneously and (2) that choice behavior was consistent with independent point processes for each of the two intervals competing for control of choice actions, with a small but systematic bias in underestimating whichever interval appeared second on each trial, indicating a capacity but also limit to multitasking of temporal information (article link).

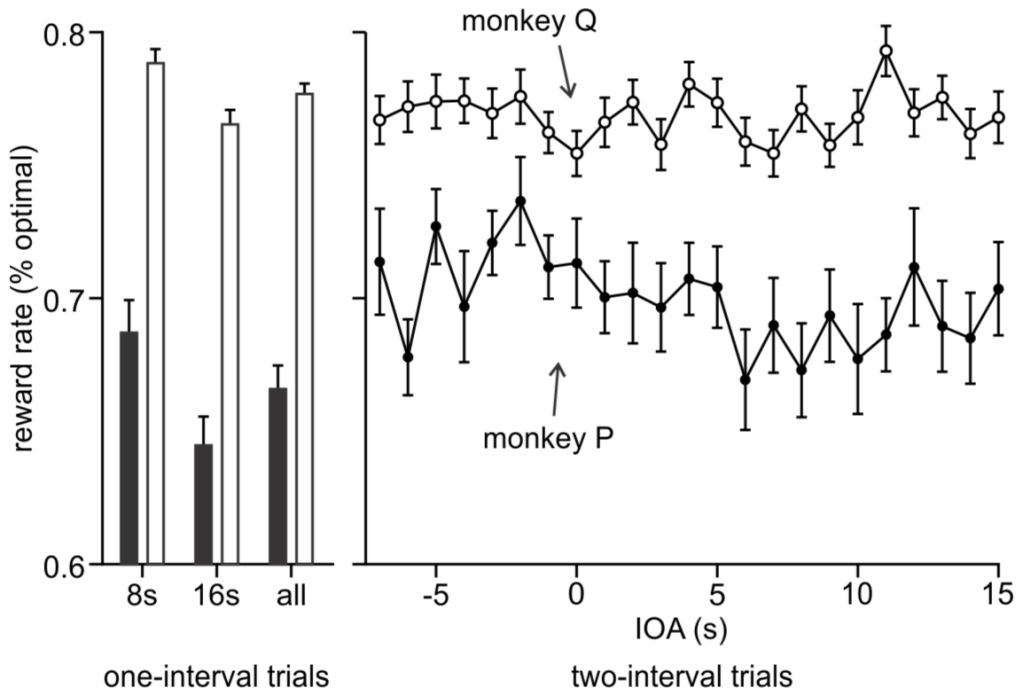

In a concurrent interval timing task, monkeys were able to flexibly and accurately time multiple long temporal intervals. When only one interval was presented (left), subjects more accurately timed the shorter 8-s interval than the longer 16-s interval, reflected by an obtained reward rate closer to optimal. In two-interval trials (right), the 8-s and 16-s onset times were randomly varied between an interval onset asynchrony (IOA) of -7 s (8-s interval appeared 7 s before the 16-s interval) to +15 s (8-s interval appeared 15 s after the 16-s interval). Subjects maintained similarly high reward rates as in one-interval trials, despite having to flexibly track both 8-s and 16-s intervals.

Then, after collecting in vivo single unit electrophysiological recordings performed during this task, I constructed a generalized linear model with autoregressive terms to model neuronal responses and discovered individual neurons in some but not all regions of dorsal prefrontal cortex persistently encoded temporal information in the form of monotonic ramping changes in firing rate, while simultaneously responding to ongoing sensory, motor, and reward events with transient changes in firing rate. This work implicated the prefrontal cortex as a critical locus for tracking the evolution of internal estimates of elapsed time, even while simultaneously representing other potential behaviorally-relevant environmental variables.

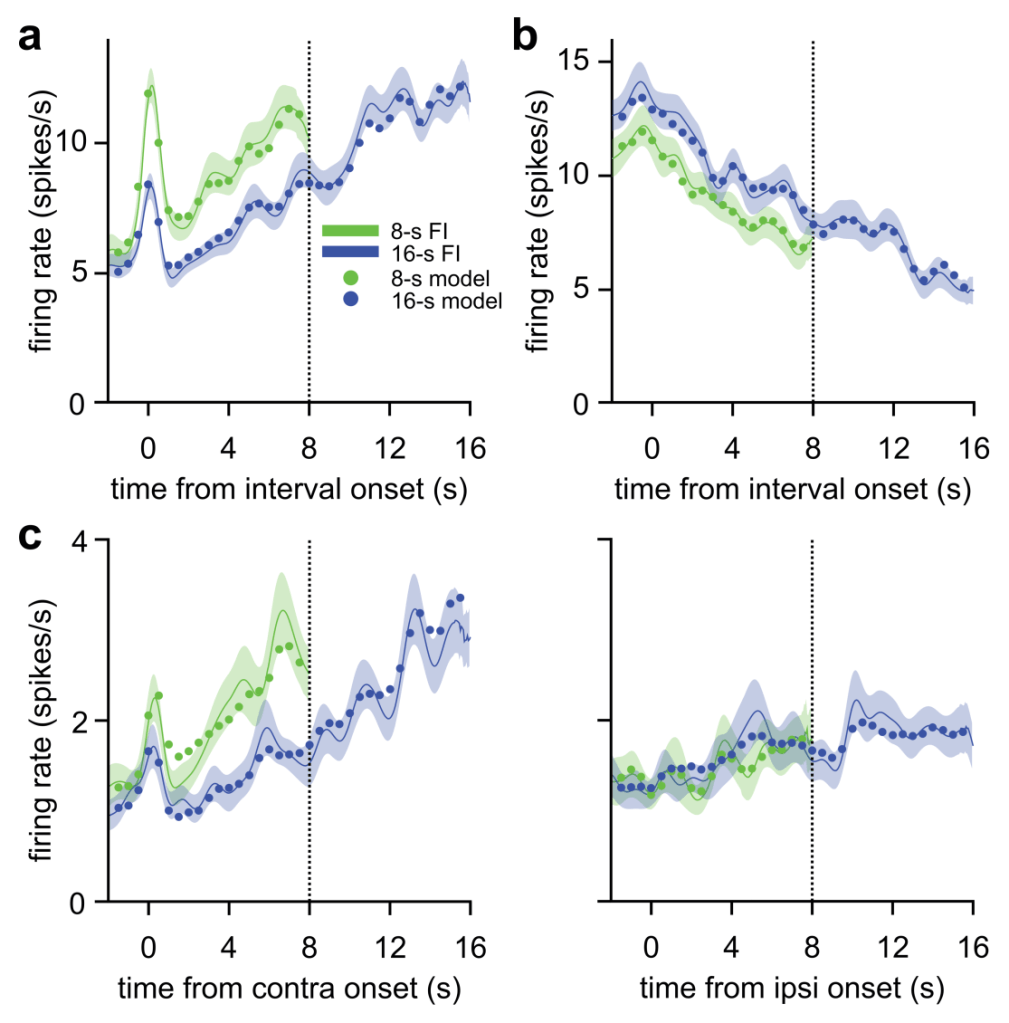

Neurons in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex encoded elapsed time through ramping changes in firing rate. Animals tracked 8-s and 16-s fixed interval targets, indicating with eye movement choices when they had judged at least 8 or 16 s had passed, respectively, since the target onset. Even while animals withheld behavioral responses, neurons showed timing-related ramping activity. Some neurons ramped irrespective of spatial position (a and b), while others selectively timed for particular target positions in visual space (c; contralateral and ipsilateral indicates position of target in visual field relative to the hemisphere of neural recording). An autoregressive time series generalized linear model fitting neural activity to sensory, motor, reward, and timing variables provided a good fit to neural data (circles).

I also worked in Professor Lee’s lab with Soyoun Kim (currently Staff Scientist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine) on experiments investigating how prefrontal cortex sensorimotor neurons respond to motivational changes in a self-control task, using drift diffusion modeling as a framework to understand how sensory evidence and value information drive neural firing rates that promote action initiation.

Decision making in simple competitive games

At Yale University, I worked with Tim Vickery (currently Associate Professor at University of Delaware) in Professor Marvin Chun’s lab (currently Professor of Psychology at Yale University) on experiments using fMRI to examine reward representations in human participants playing a simple binary choice game against simulated reinforcement learning opponents that were trained to exploit decision biases. In the first study (article link), multivoxel pattern analysis revealed that representations of trial outcomes were ubiquitously represented across the brain, indicating reward information could influence neural processing in almost all cortical areas. In the second study (article link), we found that these representations of past reinforcement outcomes were sensitive to context: participants encountered two distinct simulated opponents, and past trial outcome history was represented and decodable independently across the two opponents.

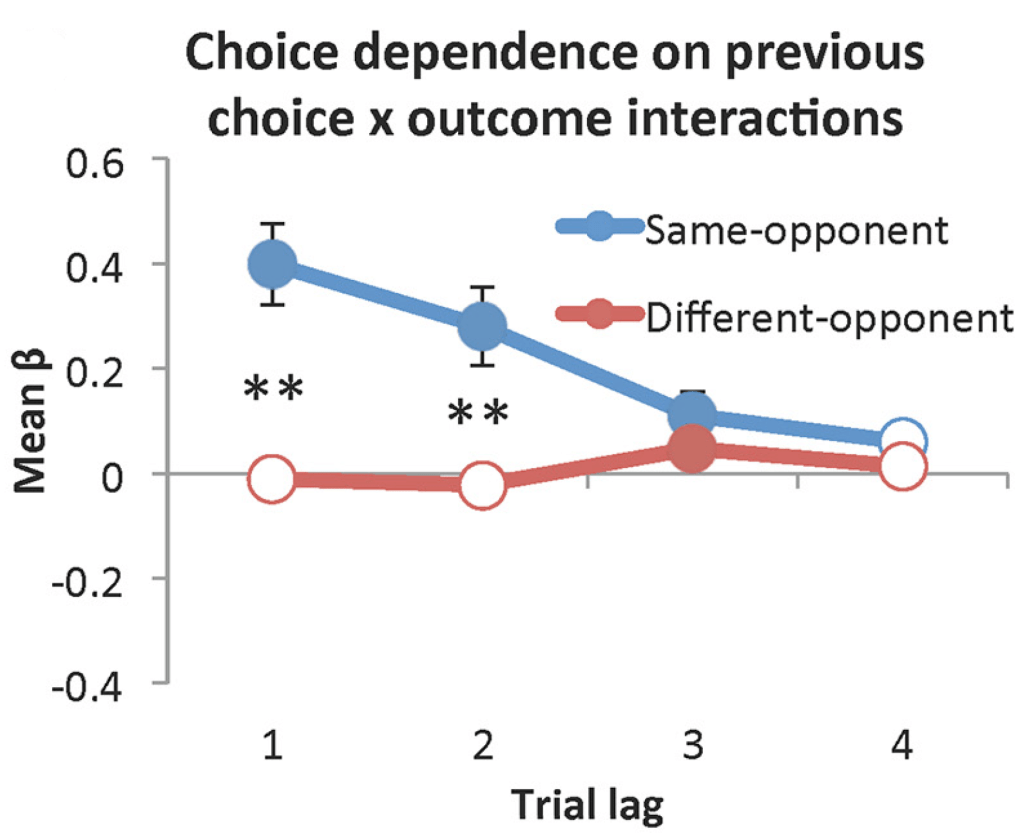

Human participants played a binary choice “matching pennies” game against two distinct simulated opponents. Participants were tasked with predicting whether their opponent would choose heads or tails and themselves picking the same, while the simulated opponents used independent reinforcement learning algorithms with a four-trial memory to predict the participant’s next decision and choose the opposite. As evidenced by opponent-specific choice dependence, participants treated the two opponents independently, and neural activity related to rewards was similarly strongly dependent on opponent. Adapted from Vickery TJ, Kleinman MR, Chun MM, Lee D. Opponent Identity Influences Value Learning in Simple Games. J Neurosci. 2015 Aug 5;35(31):11133-43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3530-14.2015.

At the University of Arizona, I wrote my undergraduate honors thesis, “Prior Beliefs and Experiential Learning in a Simple Economic Game,” on work I completed in Professor Alan Sanfey’s Neural Decision Science Lab (currently Professor at Radboud University), demonstrating that the choice behavior of participants in a simple two player competitive economic game was influenced by both expectations and experience of fairness, with those expecting fairness willing to punish unfairness of other players even when it reduced their own earnings. I also worked with Luke Chang (currently Associate Professor at Dartmouth University) on experiments examining the neural basis of guilt aversion in a competitive economic game (article link), using fMRI and behavioral tasks to test a model that proposed participants would be willing to forego some monetary reward to avoid feelings of guilt that would arise from being greedier and more unfair to other participants.

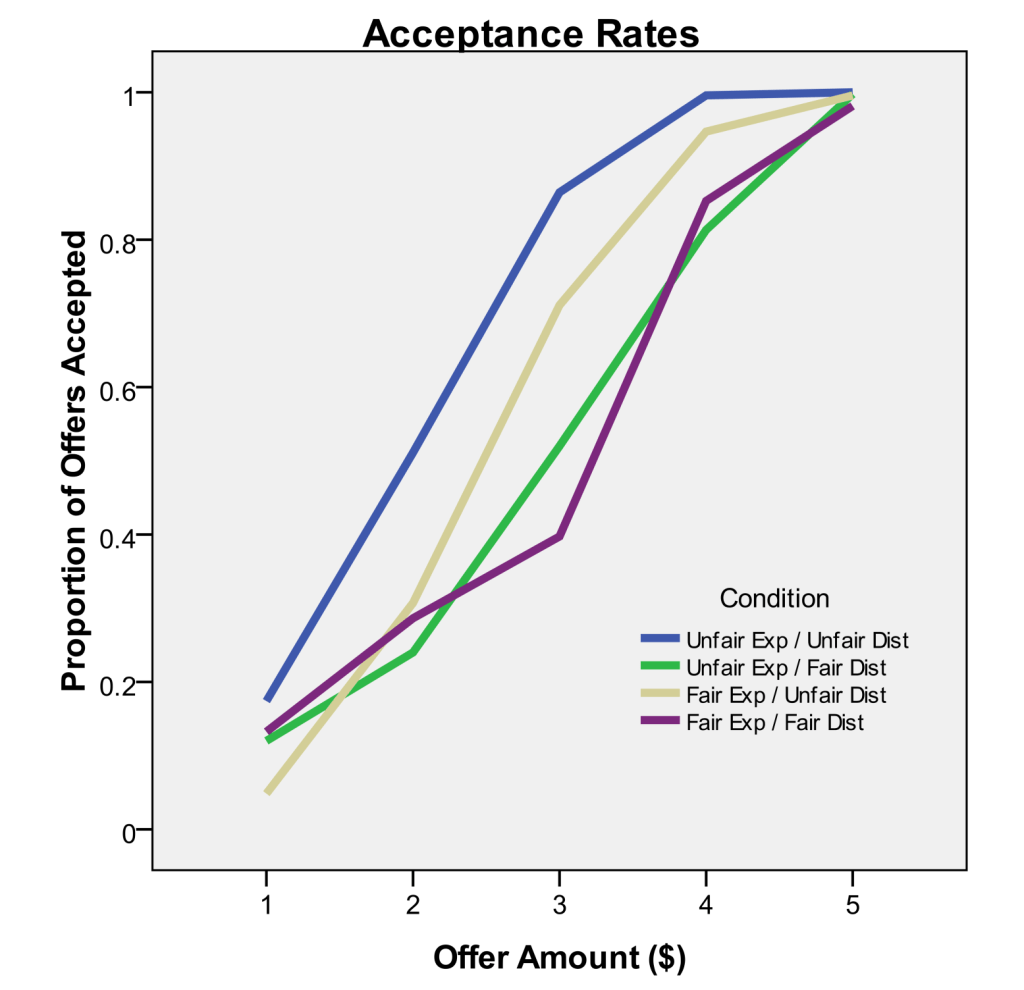

Participants completed trials of the “ultimatum game” against fictitious opponents, in which the opponent offered the participant $1 to $5 of a $10 endowment, and the participant either accepted the offer and received the offered amount, or rejected the offer and caused both players to receive $0. The instructions included a line that primed participants to expect more fair offers (“Fair Exp”) or more unfair offers (“Unfair Exp”), then participants experienced a distribution of offers that included more $4-5 fair offers (“Fair Dist”) or more $1-2 unfair offers (“Unfair Dist”). The 2×2 design revealed both the expectation and experience of fairness influences decisions in this game, demonstrated most strongly by participant responses to $3 offers that were equally common in all conditions.